In their attitudes to publishing their outputs, Taylor and McFarlane were wildly different. “Most dons, especially my colleague Bruce McFarlane, ask of an historian – how many of his pupils were placed in the first class? I asked – how many books has he written?”†

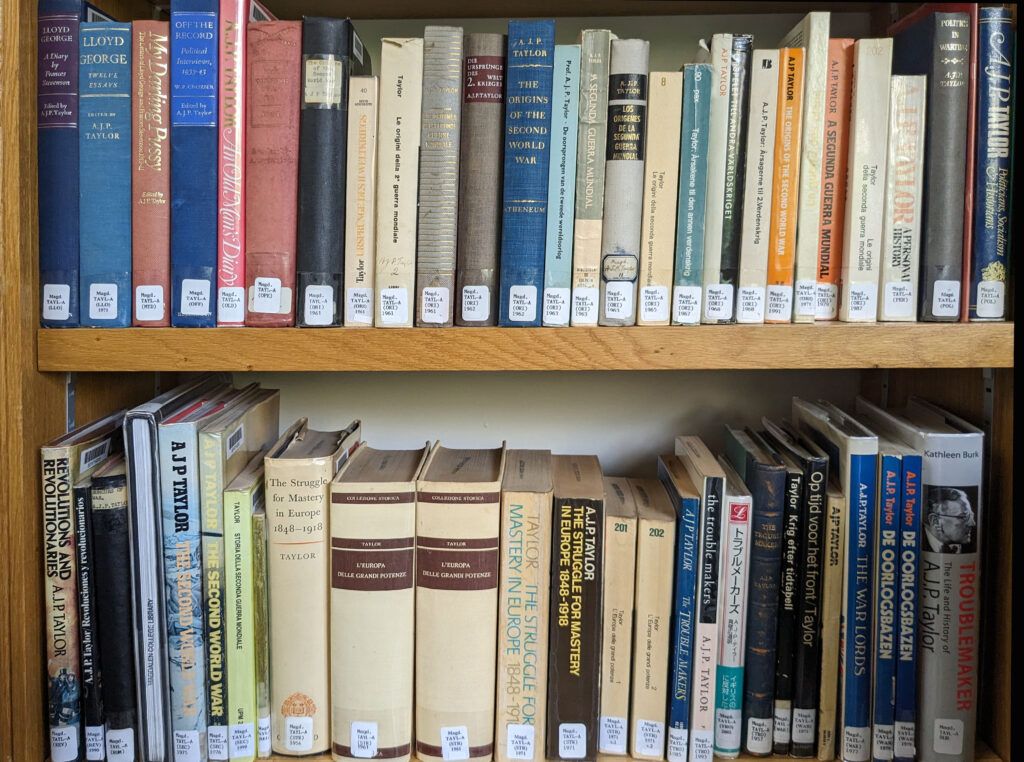

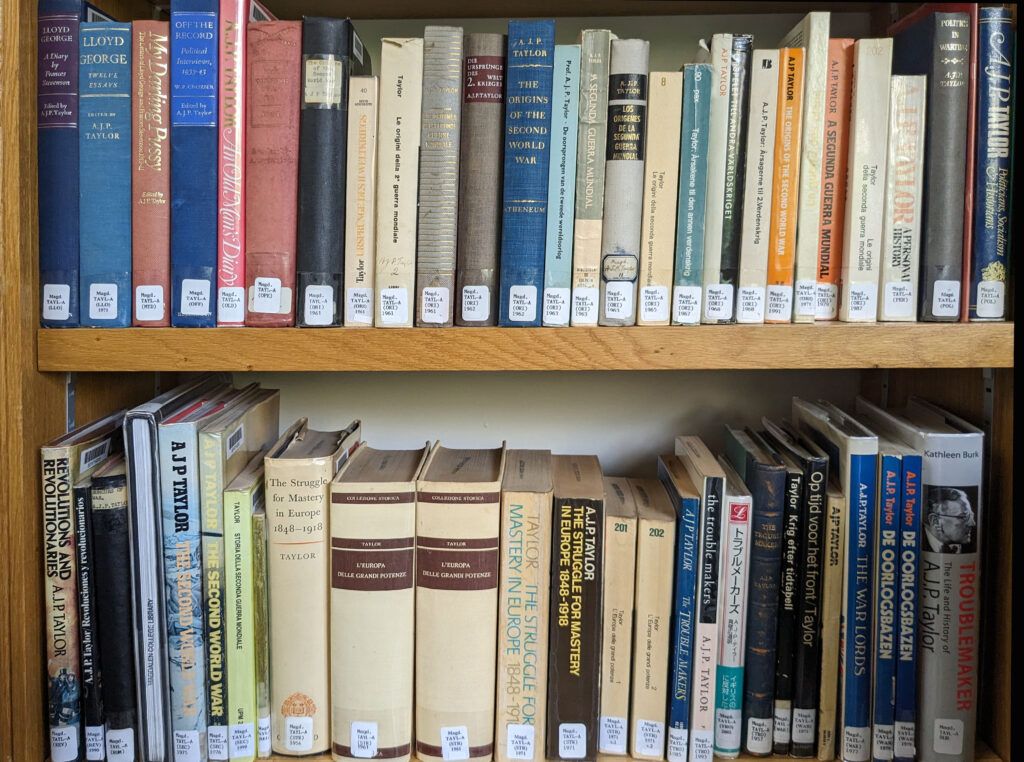

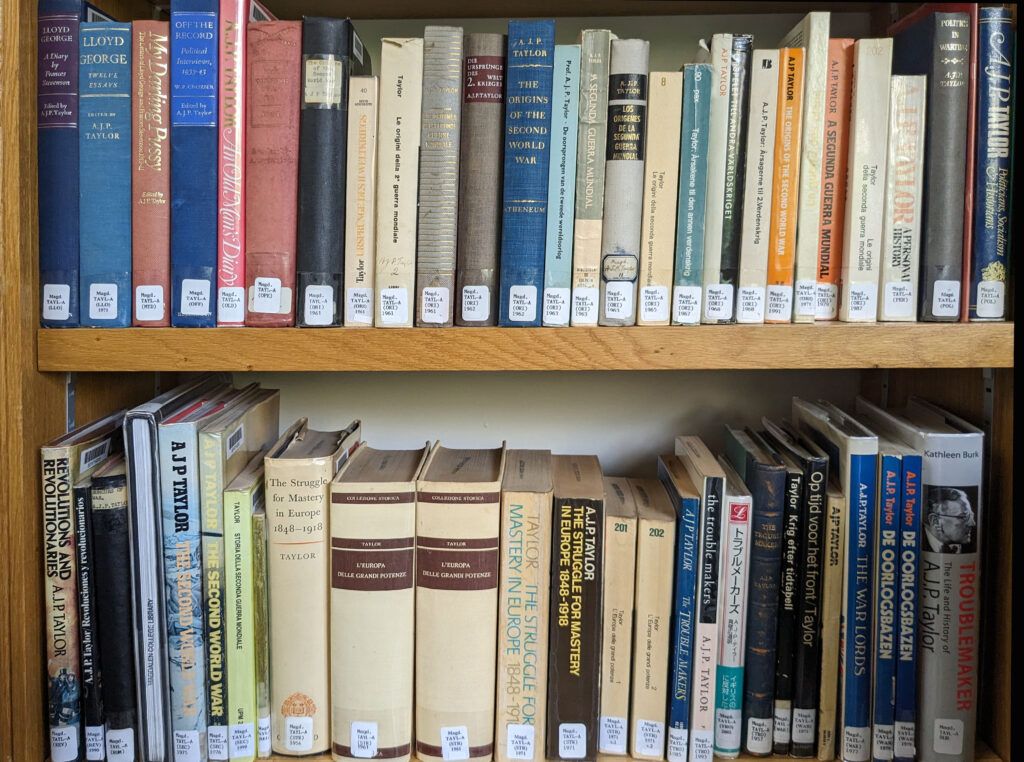

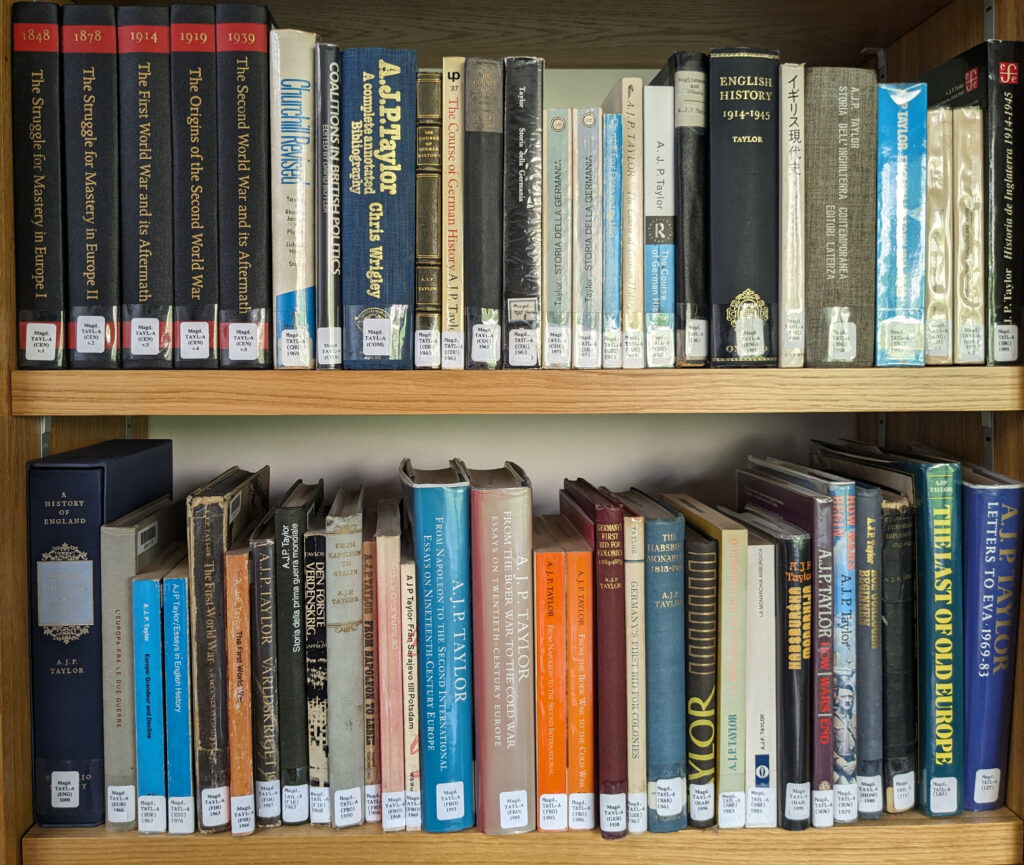

We have 85 books written by A. J. P Taylor in Magdalen’s collections, and his works have been translated into many different languages.

† Taylor, A. J. P. (Alan John Percivale). A Personal History. London: Hamish Hamilton, 1983. Print. p. 179.

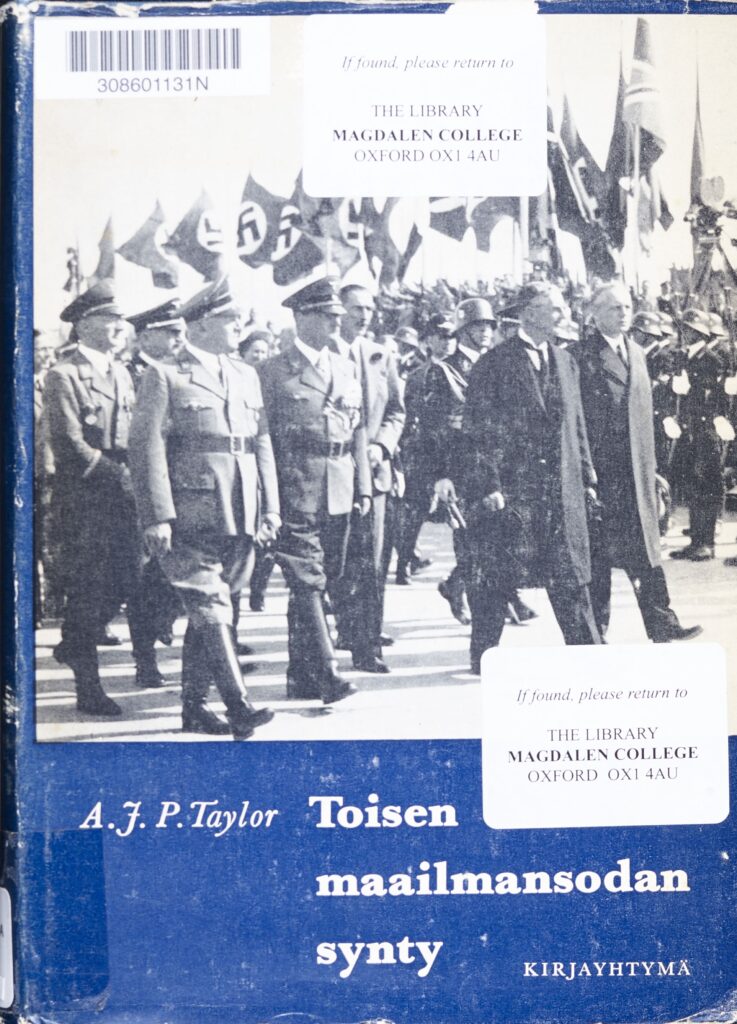

Finnish translation of The Origins of the Second World War by A.J.P. Taylor

Arguably Taylor’s most famous work, The Origins of the Second World War provoked outrage on its publication. In it, Taylor argued against the prevailing view that Hitler’s aggressive expansionist policies were the primary cause of the war, instead suggesting that the actions of other European powers, particularly France and Britain, played a significant role in enabling Hitler’s rise to power and the outbreak of the conflict. In so doing, his critics accused Taylor of being a Hitler apologist. The text has been translated into many different languages, including this Finnish translation published in 1962 – just one year after the original publication.

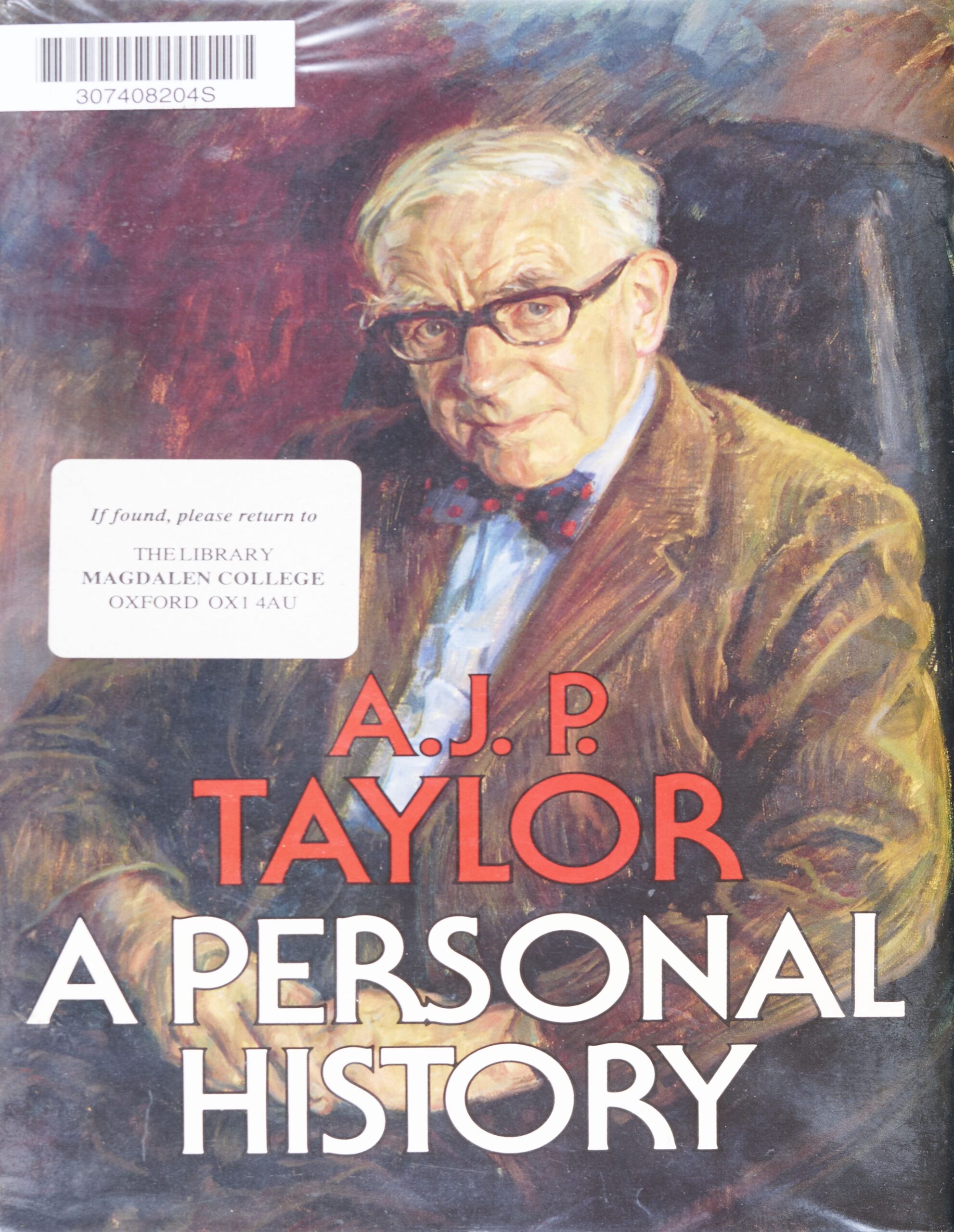

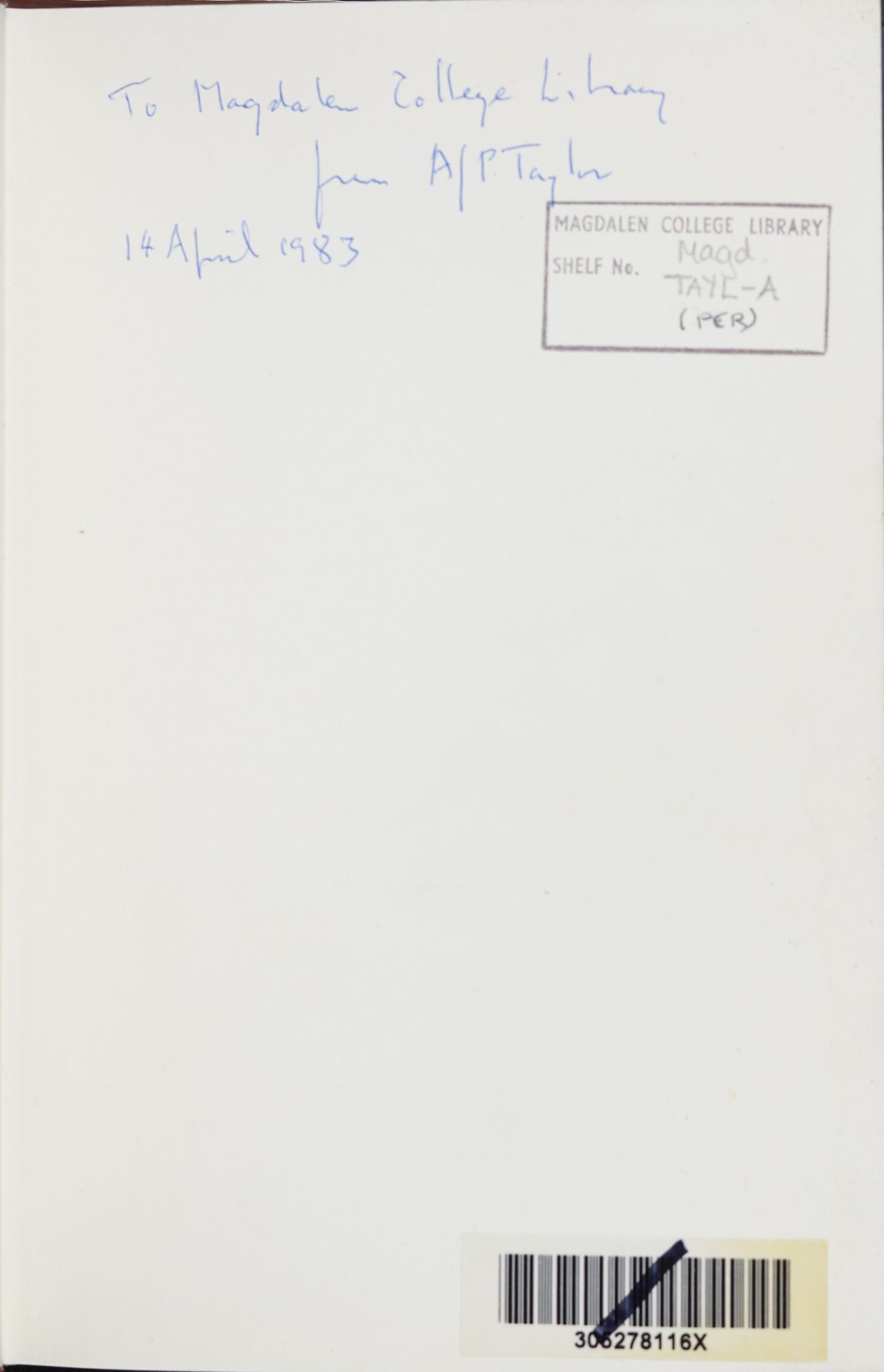

A Personal History by A.J.P. Taylor

This copy of A.J.P. Taylor’s memoir comes from our Magdalen Authors collection, held here in the Longwall Library. It was given to us by the author upon its publication in 1983. In it, we learn Taylor’s views on Oxford and his colleagues, including K.B. McFarlane. We get details of Taylor’s efforts to make changes at Magdalen – such as the admittance of women – and see his side of what McFarlane deemed ‘the Taylor crisis’ (see McFarlane’s letter to Helena Wright). The painting used for the book’s cover currently hangs in our Summer Common Room.